Many years back when I last stopped at this rare Dhaba on Sultanpur Lodhi-Kapurthala road, it was operating as one joint. Now a partition in the front verandah indicates two shops. Brothers doing what it appears is the natural thing these days – getting divided.

As I wait for a cup of tea, I catch up on whatsapp messages.

There are few messages in ‘Kisan Ekta’ group. This is a group that was formed by

my village boys last year to discuss, inform and participate in the farmers

movement. It also has been my portal into what does the rounds of social media in

rural Punjab. Last night it was the clips of the person attempting sacrilege at

Golden Temple, clips of gathered crowd banging on the doors of gurudwara

committee baying for his blood and the bloody images of the dead body. There

are a few new videos this morning. One is discussing a PIL that asks all

pension and perks of politicians to be removed. Then a video starts with a young

man beating someone whose hands and legs are tied. After a few seconds the camera

turns to someone who starts speaking of how they have caught another person

attempting sacrilege. He narrates the story, and the beating continues in the background.

The sound of traffic passing by fades. The words of the speaker in the video

fade. Only the ‘lathi’ in the hand of one who appears a young handsome turbaned

boy swings and meets a young helpless tied young body. Over and over again.

Main us bare apshabad sunda haan,

Usdi pat rakhan layi,

Hathiyar chuk lainda haan,

Usdi pat meri muhtaaj nahin.

(I hear impolite words about him

To keep his honor

I take up arms

His honor doesn’t depend on me.)

The five minute long clip shows the tied man being brutally

beaten as the speaker, the granthi of the Gurudwara, narrates how they caught this

man early morning and how the ‘sangat’ should reach the place immediately, of

how they will not hand over the person to police and of how the religious heads

should come and give this man punishment as per religious code and conduct.

Usdi gall karan wale,

sareyan nu sunda haan,

Pujari vidwaan chele yodhe,

Bas ose nu hi nahi sunda.

(Those who talk about him

I listen to them all

Priests, scholars, followers, warriors

Only to him I don’t listen)

This clip is from somewhere in Kapurthala. A short distance

away from where I sit and sip my tea. I check the local news. People have ‘listened’

to the call of the ‘priest’ and have gathered at the village of this incident. Police

is there as well. The person is still in captivity of the ‘sangat.’ One key Kapurthala road is already blocked. I remember

the roads all over Punjab getting blocked a few years back the day of another

sacrilege and following police action. I pay for my tea and turn my car back

towards home, towards Sultanpur Lodhi, towards Nanak’s town.

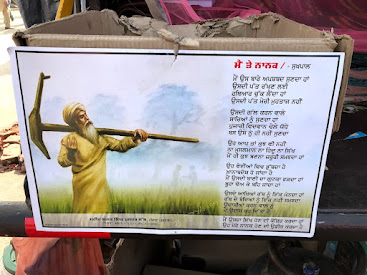

It was a day of celebration at Singhu. The sangat was organizing

a Nagar Kirtan. The tractor-trolley-tent township was cleaned and decorated as

best as possible and everyone was in a positive, cheerful mood. Few friends from

Delhi had come that day. We were walking along the lanes of this place of

resistance, a place of hope, a place of pilgrimage, when a young girl carrying

a small poster with Sukhpal’s Main Te Nank passed by. I stopped her and asked her

if she had read the poem on the poster. She said no. I requested her that she

should, and I requested her father who was standing next to her that he should

read this with her and explain and understand.

I wish I could hit a pause button over Punjab and like that

little girl, ask all of them to read Sukhpal (if not Nanak).

The road runs parallel to the solitary train track between

Kapurthala and Sultanpur Lodhi. Mostly local trains use this track, with an occasional

Jammu Tavi. In 2019, on the occasion of 550th birth purab of Nanak, the one

room railway station of Sultanpur Lodhi was renovated and a grand hall built. It

played religious movies during the Gurupurab celebration. It was meant to be a

reception area of the new station but time stands still in that empty hall now.

A new train was started on the occasion from Sultanpur Lodhi to Delhi, aptly

named Sarbat Da Bhala. The one time I travelled by it, it took 20 hours for a

journey of 8 hours. I was told that it was an isolated incident, and that train

usually was on time. In another four hours it will be the ‘right’ time for

Sarbat da Bhala to cross from where I am right now. But from where I am right

now, it seems Sarbat Da Bhala is now ‘forever delayed.’

Oh aap taan kuch vi nahin,

Na Musalmaan Na Hindu Na Sikh,

Main hi kuch banna jaroori samajhda haan.

(He himself is none

Not Muslim, Not Hindu, Not Sikh

But I think it is important to be one.)

I have driven about a mile when I see a familiar face

standing by the road. I slow down and stop, and reverse about ten meters, roll down the window

and greet Bhullar Sahab.

A soft spoken, erudite, well reasoned and well seasoned card

carrying communist. That is Balwinder Singh Bhullar. One of those associations made

at the Kisan Morcha. It was an easy association to make from the very first

meeting and fireside discussions at Singhu border early January 2021. He is district

president of Kirti Kisan Union and a state committee executive member. I spent

hours listening and debating communism with him. My notes from those long discussions

with him only carry three points. “Since we want privatization, why don’t we

privatise governance.” “Khanda saadi virasat hai, lal jhanda saadi siyasat hai.”

“Communism is sarbat da bhala.” Despite the red blooded comrade that he is, he

is easily likable.

Discussions with Bhullar sahab turned to debates many times,

but reason never left the room (or the trolley in this case). The same wasn’t always

true of the flag-carrying-stalwarts of the ‘right’ or the ‘panth’ there. One evening

a day or two before the 26th January (the one that could have been!)

I found myself among a few youngsters eager in their energy to ‘capture Delhi.’

My boring laments of sticking to what the SKM leaders decide and keeping the

morcha non-violent proved a bit too much for one of the group. ‘Aida dadha

rakheya, eh kaaton rakheya, sharam karo, Singh Bano.’

A surprised Bhullar sahab steps inside the car. His greeting

is warm and his smile sincere and affectionate. He was waiting for a bus to go

to Sultanpur Lodhi. It’s only a ten minute drive at my usual speed but with Bhullar

sahab and an opportunity for news on SKM I drive slower. On enquiring how is rest

and break after morcha, he replies like only a true red could. “Morcha khatam

nahi hunda. Kisani Sangharash sampooran inquilab da ik pada si.’ For him the

morcha is never ending, the fight an ongoing continuous endeavor. The distance

goes by fast with Bhullar sahab. As we reach the bounds of Sultanpur Lodhi we cross

Gurudwara Sant Ghat. This is where Nanak appeared three days after disappearing

into Kali Veyin. The history board at the gurudwara says his first words after

he reappeared were ‘na koi Hindu, na koi Muslim’. The question that no one asks,

or answers is – did say he say there is a third?

Oh veyian vich dubda hai,

Khanabadosh ho janda hai

Main osdi bani da gutka fadda haan

Booha dho ke baih janda haan.

(He drowns in rivulets

Wanders from place to place, becomes omnipresent.

I hold the book of his hymns

And hide behind a closed door.)

‘What brings you to Sultanpur Lodhi?” I ask Bhullar sahab as

I near the place where he has asked me to drop him. I should have guessed the

answer. ‘Inquilab.’ He is here to deliver copies of December 21 issue of their magazine

‘Inquilabi Sada Raah.’ I ask for and get a copy. He walks away, on his continuous

endeavor.

The link road to my village is next to Gurudwara Ber Saheb,

the place where Nanak sat under a Ber tree and meditated on ‘His’ name for

nearly 14 years. I navigate the Sunday crowd, greet those serving chai langar

to passing traffic, and exit for the link road. The Darshani Deori to the Gurudwara

is on the link road. As I cross, I glimpse at the white structure where we bow in

Nanak’s name.

Usde aakheyan rab nu ek manda haan,

Rabb de bandeyan nu ek nahin samajhda,

Udaasiyan karan wale nu,

Main udaas kar ditta hai

(He says and I believe God is one

God’s creation mankind, I don’t treat as one

The unweary traveller of all directions

Is melancholy, worn down, with my actions.)

‘It has been a long wait for justice.’ ‘Hundreds of cases of

desecration and sacrilege and no culprits have been punished.’ ‘It’s the system

and government that has let us down, these deaths are their responsibility.’ ‘The

system and government has failed us.’ The list of arguments and justifications is

long.

I enter the last stretch of road before reaching home.

Somewhere nearby the lathi swings, somewhere the swords are raised, and the

jaikaras issued, the pitch and fervor reach a crescendo and a question goes

unsaid, unheard - ‘Haven’t we all failed Nanak?’

Main usda Sikh hon di koshish karda haan,

Oh mere Nanak hon di udeek karda hai.

(I try to become his Sikh

He waits for me to be Nanak.)

(at Singhu - December 2020)